I want to discuss how as businesses, we can stimulate nonlinear growth if we can remove friction and surf waves. I’ll kick things off by diving into economic theory, specifically returns to scale.

Then, the impact removing friction can have with a case study, and more importantly how we can begin to reduce friction within our businesses. I’ll finish off by exploring the idea of surfing waves and delve into a handful of future trends to look out for.

In this article, I'm going to be talking about removing friction and surfing waves, and how as businesses, if we can do both of these things, we can stimulate nonlinear growth.

I'll start off with a little bit of economic theory, I'm going to talk about returns to scale.

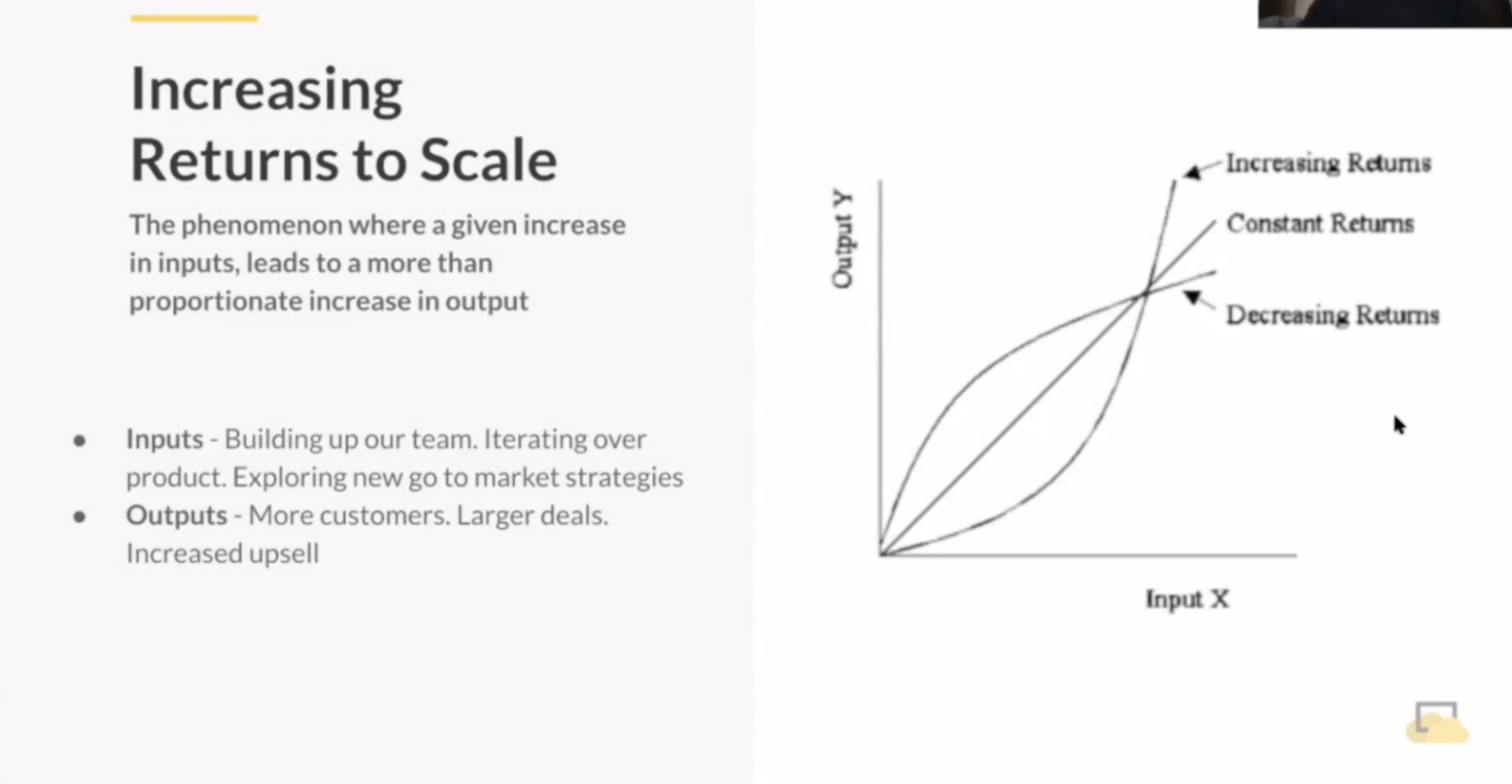

Increasing returns to scale

If you look at the graph on the right-hand side, it's fairly simple, you can see there are three types of returns to scale; increasing returns, constant returns, and decreasing returns.

Obviously, as a business, we're looking for the very nice graph, the increasing returns. This is the phenomenon where a given increase in inputs leads to a more than proportionate increase in outputs. Let's just explore a bit about what types of businesses would do this.

If we start with the simplest one, a micro-business one-man-band kind of thing, you're probably likely to see constant returns where just adding a new tool or an extra person would literally have a proportionate effect to the returns that you'd be able to achieve. But that doesn't really last forever.

Decreasing returns

A lot of businesses fall into the camp of decreasing returns and I've experienced this myself in my own career running a digital agency previously, where although it started out very profitable with everyone being fully billable and a lot of us running and managing our own projects.

As we got bigger and added more people and more processes and some people that were not billable to client projects, we saw our margins actually decreased over time. The bigger we got, the less we began to make, which was quite painful.

But as a tech company, and particularly as a SaaS tech company, we should all be looking at increasing returns to scale and how we can achieve that. Let's look at what the inputs to that might be.

Inputs

- Firstly, building up your team, bringing on people with more experience, greater talent, as you get bigger and more attractive to hire - that's an obvious one.

- Iterating over your product, releasing new features, making those features better, listening to your customers, and just getting a tighter and tighter product shipped in another key input.

- Inevitably exploring new go-to-market strategies, looking at new verticals, and maybe even new products and complementary products, as well.

Outputs

The likely outputs of all of those inputs would be:

- That you can vastly increase the number of customers that you're working with.

- By adding features that may be more applicable to say, enterprise deals, larger deal sizes, higher ACVs. And

- Obviously, as you build up your number of customers, you can increase your upselling opportunities to them and this is all how we get increasing returns to scale.

The cliche of disruption

If we take a bit of a VC cliche here, the cliche of disruption is typically said to be something like building a 10x better experience.

But what do we really mean when people say a 10x better experience?

Well, to my mind and I believe to most of us, this typically means that we are removing friction from an existing process, and by removing that friction, we can actually stimulate increased frequency of use of our products, but we can also broaden our reach across the market.

This is really also known as product-market fit.

Removing friction can dramatically grow the addressable market size

A byproduct of removing friction and creating a better product is we can also really grow our addressable market size. I'm going to show you an example that we're all very familiar with.

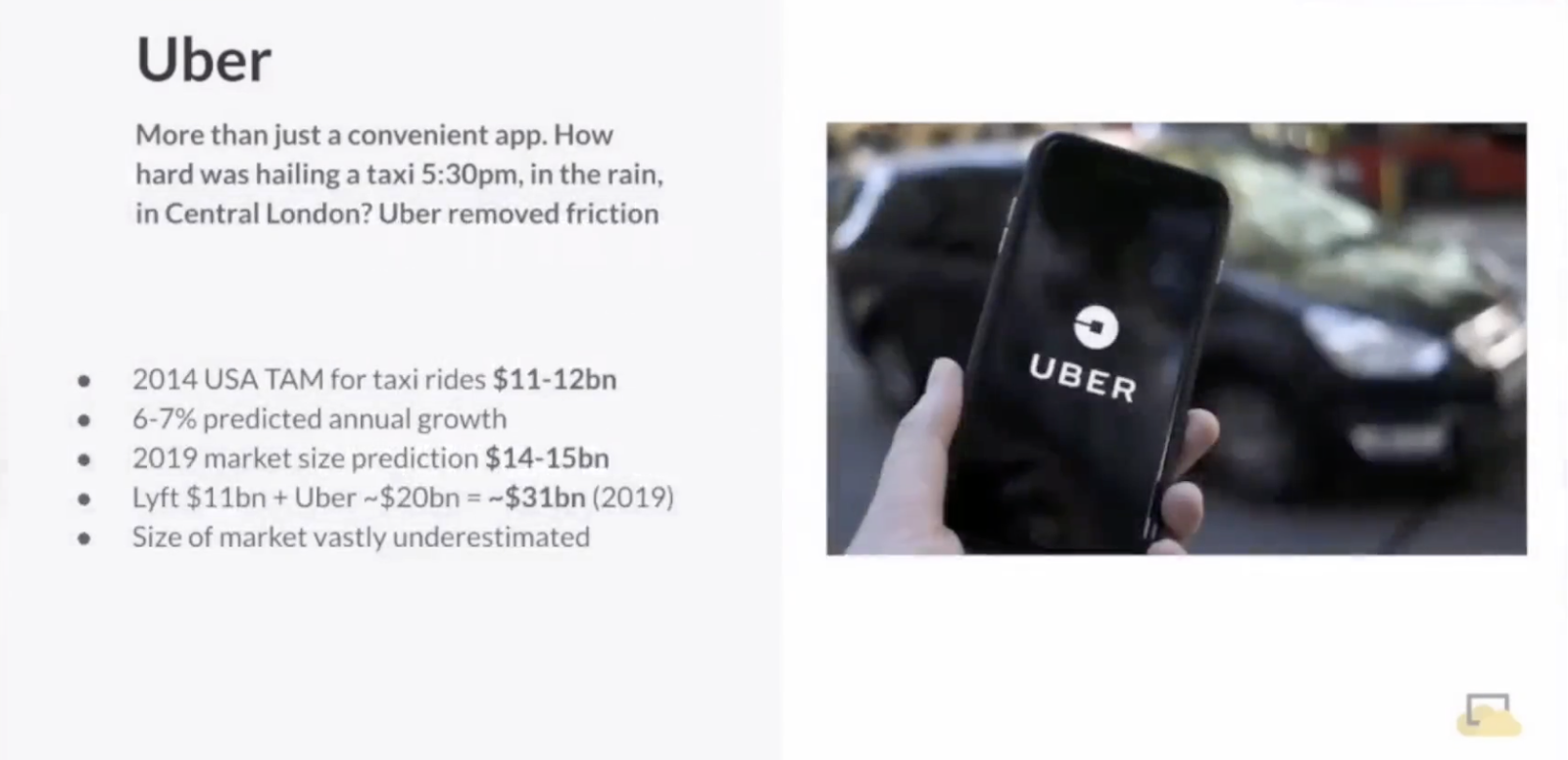

Uber

If we look at Uber, it's more than just a convenient app for ordering a taxi. Many of you may not be able to remember this but if you think back to pre-Uber days, how hard was it hailing a taxi in London or New York at 5:30pm in the rain on a Friday evening? Extremely painful.

The number of people who couldn't find a cab or people were bumping in the way and actually stealing cabs from. Or maybe it's kicking out time of a bar or nightclub and everyone's going to the taxi rank and there's a huge queue and not very many cabs.

Uber removed a huge amount of this friction, but they didn't just make it slightly more convenient they also changed the way people thought about how they would use taxi cabs.

So actually, we've seen people thinking maybe they will use it instead of driving their own car, or maybe (not great for the environment) using it instead of public transport. Because that friction had been removed to such a good degree and it was so much more reliable and actually more cost-effective, people started to use it a huge amount more.

The numbers

The prediction

Let's look at the numbers to prove that. Back in 2014 in the US, the addressable market size as analysts predicted for taxi rides was $11-12 billion, they predicted around 6-7% annual market growth of that - not really allowing for any of this disruption to happen.

That was probably based on cities growing larger, greater urbanization, population growth, people getting higher salaries, being able to afford them more. The normal stimulants of fairly decent but modest growth.

By my maths, in 2019, the market size prediction by analysts for taxi rides would have been $14-15 billion.

The reality

Lyft, which is the number two in this category, actually managed to achieve $11 billion of revenue in 2019. Uber doesn't publish its numbers, but through other numbers, we can predict what they would have done, it will come in around $20 billion, which is $31 billion just in their segment alone, that doesn't even allow for the incumbents which would also increase that more.

You can see the size of the market had been vastly underestimated, but not necessarily for bad reasons. It's just the disruption and the removal of that friction had not been accounted for the changes in behavior that would follow.

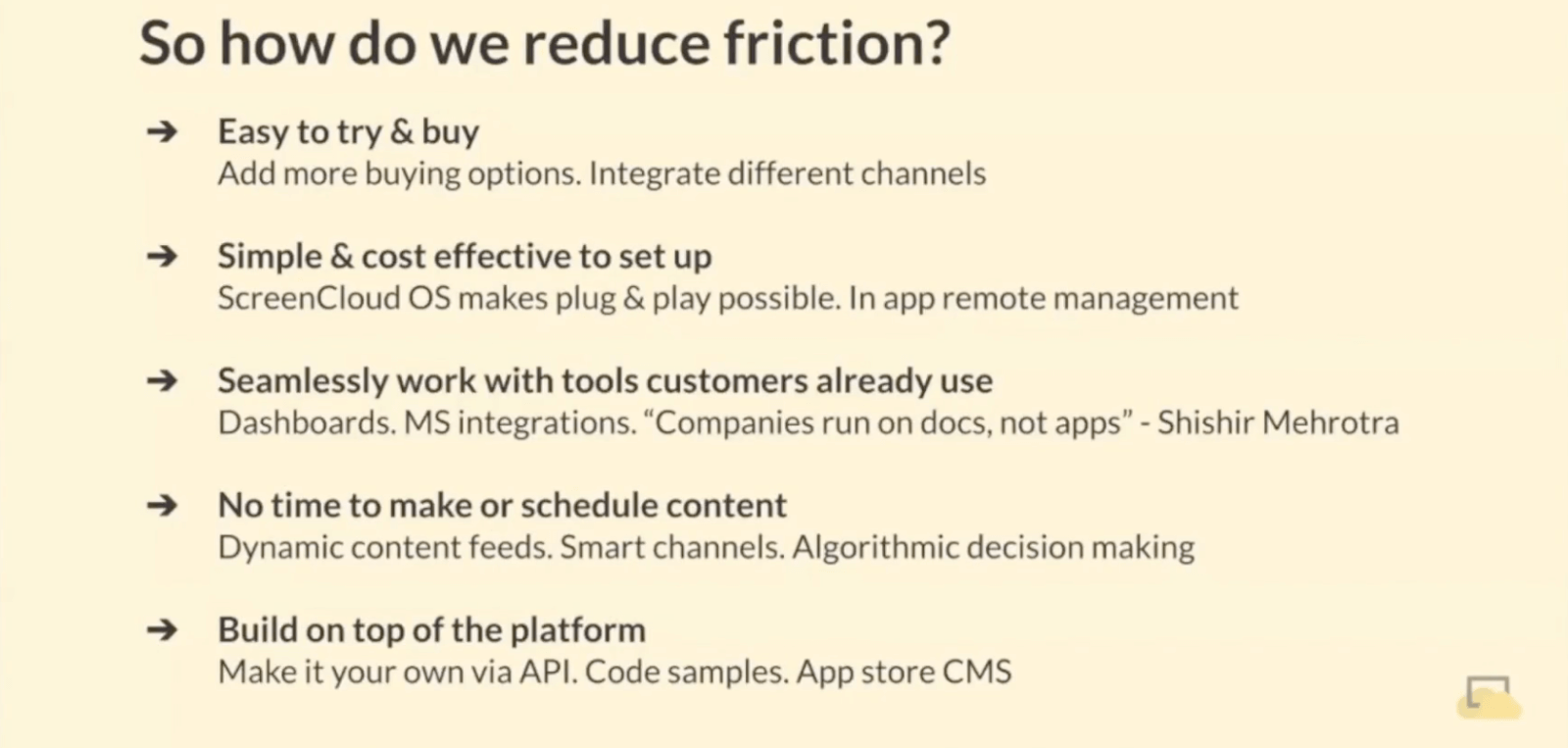

So, how do we reduce friction?

At Screencloud this is another big thing that we look at, how can we reduce friction to increase our market size?

Easy to try & buy

We make it very simple for people to buy our products. We have free trials, you can just sign up with credit cards, you can buy one screen, you don't have any limits, and our incumbent market typically is more interested in the larger deals, in selling through reseller channels, and is not really very accessible - you can't just go online, try something and buy it.

So we're always looking at how we can reduce that friction there.

Simple & cost-effective to set up

We've also looked at set up and setting up screens usually was quite costly, was commercial-grade hardware, which not many people can easily buy, you couldn't buy on Amazon or anything like that.

We've used normal screens with things like Amazon Fire TV, everyone is familiar with that technology, and can buy it from Best Buy, Amazon, nice and easy, and set it up themselves.

So we've massively reduced the setup and who can actually do that set up.

We're also exploring new things, we're actually building our own operating system, which makes plug and play more possible and things like that. So we constantly iterate on how we can make that easier.

Seamlessly work with tools customers already use

Another really interesting insight, which I think is worth pausing on for a moment and talking more about is seamlessly working with the tools that our customers already use. I think often as product people, we can be guilty of trying to reinvent the wheel or land grab for too many features.

There's a really interesting insight from the ex-CEO of YouTube when he was working at Google called Shishir Mehrotra, who is now the CEO of Coda.

I was listening to a podcast where he talked about this and his insight was that companies run on docs, they don't run on apps. What he means here is that actually, if you look at any kind of project or think of a project in your own company, imagine you're running customer events or something, how are you planning that out?

You will be using some apps, but actually, a lot of the work will be done in spreadsheets, in meetings, maybe that's on Zoom and things like that, through chat, which I guess is an app as well, and docs could be considered an app.

But what I think he's getting at here is that spreadsheets, PowerPoints, Word documents, email, these docs are actually how people get things done. And in the bigger companies, it's even more prevalent than say in a cool startup which often probably will be using apps first.

We've decided at ScreenCloud that rather than trying to reinvent what people already do, we should just integrate with where they already are doing the work they do every day, and just pull from there. So we work with existing dashboards, Microsoft integrations, and anything like that. We try and reduce that friction.

No time to make or schedule content

We've also found that people don't really have time to spend authoring and thinking about content, and they want things to be automated.

So we're working on ways of actually making decisions for people based on business rules, rather than asking people to schedule things all the time. Building more automation is reducing the friction by meaning people don't actually have to spend time planning all of this out and we can actually use best practice and do it smarter and faster.

Build on top of the platform

We've also opened up our platform. We actually re-architected the whole platform a couple of years ago, and built everything with a graph qL API, it was API first, which means that every feature inside ScreenCloud is available to customers via API.

We've put out code samples and things like that, and that has also massively reduced friction. Where customers were previously waiting for features, maybe quite unique and bespoke features that we probably didn't have on our roadmap, they can now go ahead and build them themselves which makes the whole platform more sticky.

It means they rely on it more and use it more and therefore, we see quite a lot of account expansion and things like that happening as a result.

Those are some examples of what we're doing at ScreenCloud but I think they're quite universal. I would encourage you to look at your own business and look at each area of friction and how you can keep improving and iterating against that.

Surfing waves & trends

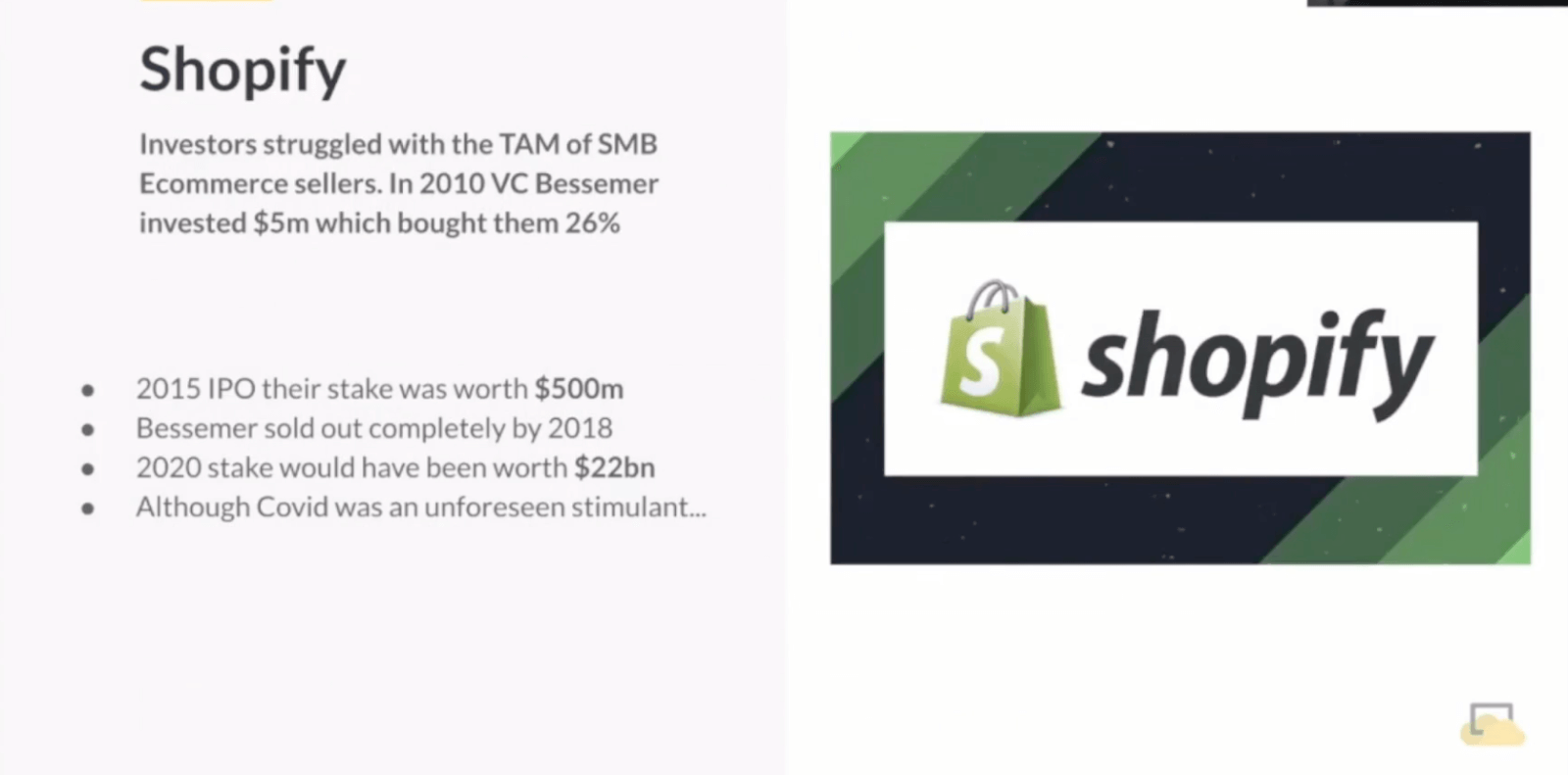

I'm going to switch tack now and talk about surfing waves and trends. An example here I'm going to talk about is Shopify.

Shopify

When Shopify began, they actually bootstrapped the company and were profitable. They were based out of Canada, so they weren't in the valley and they really struggled when they felt that they wanted to take on some investment to fuel growth in finding any VCs that were very interested in them.

The problem

The problem was investors really struggled with the addressable market and size of opportunity of small and medium-sized businesses on e-commerce. They could see them not selling very many, maybe only wanting to go to big brands, that often they would be going bust and high churn.

Really, it was a very big struggle for Shopify to raise any money.

The turning point

They had a stroke of luck when they were introduced to a new partner who had just joined the VC firm Bessemer in 2010. I think due to a strong personal relationship with the founder, they hooked that deal in and Bessemer invested a very small amount, $5 million, which actually bought them 26% of Shopify in 2010.

Just think about that - they were already profitable and for just $5 million that got a quarter of the company.

Shopify went on to do great things and in 2015, they IPO'd. The Bessemer stake, that $5 million stake, had dramatically increased in size to $500 million dollars, which is an extraordinary return.

What's interesting, again, about the story is that even at that point, Bessemer, their own investor, still wasn’t completely convinced about the opportunity that lay ahead and they started to sell. By 2018, they completely sold out of their stake.

Now, if they had held on to their stake, today it would be worth $22 billion, which is extraordinary. I think it's quite interesting to see that they just couldn't quite see that far ahead even as people who were there.

COVID has obviously been a huge stimulant but let's start to look a bit more at the e-commerce numbers.

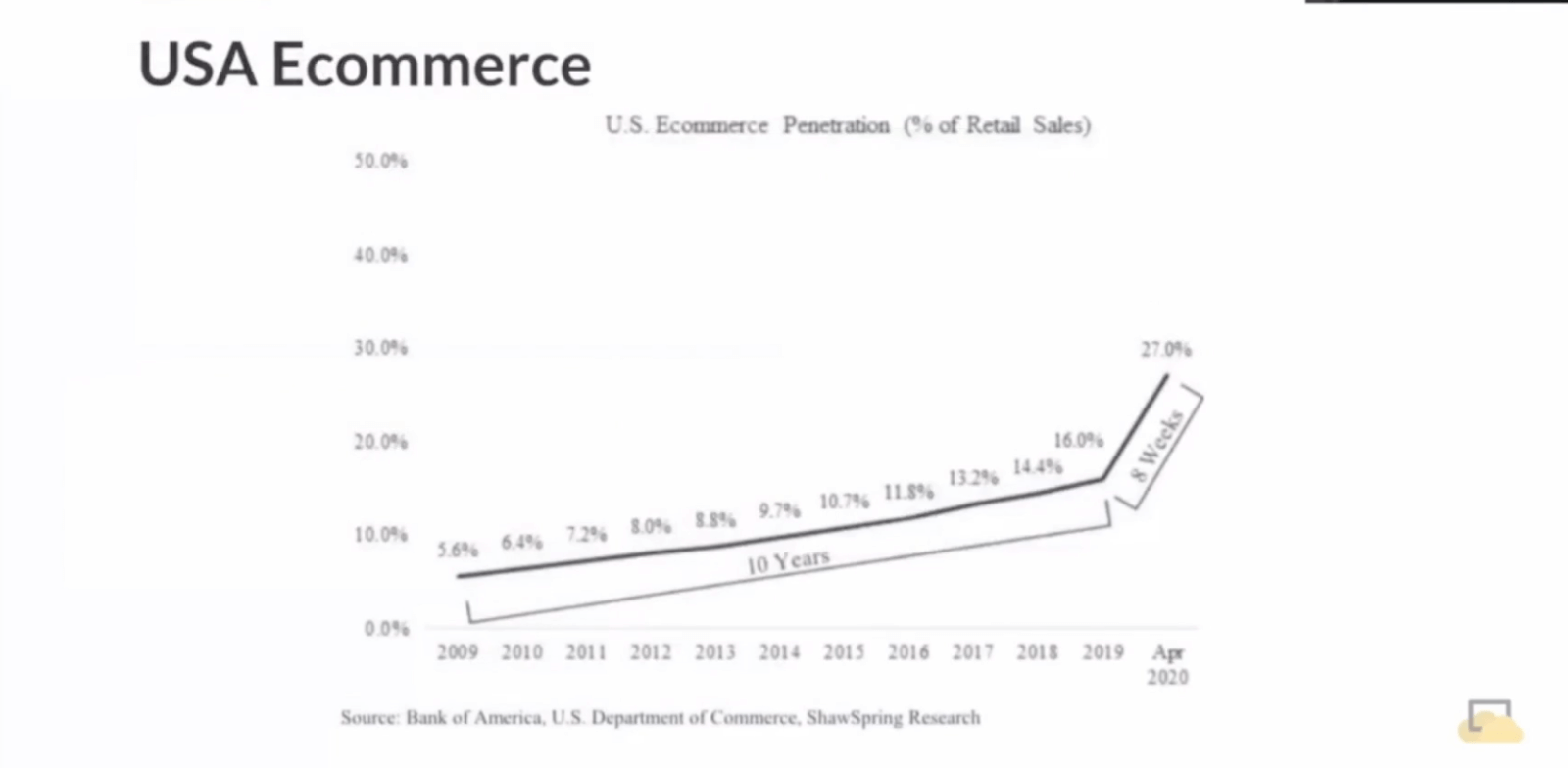

USA Ecommerce

Back in 2009-2010, when Shopify was out to market, e-commerce penetration, just in the US alone, was only somewhere between five and a half and six and a half percent. Really tiny.

I think most people will have thought that actually, they still had a very long way to go. Obviously, that was expanding, and Shopify was doing very well, clearly outperforming the market but by 2015, that had only gone up to 10 and a half percent. So really, very small penetration of retail sales.

And still, people were betting against the internet, which in my experience is not a very good idea. By 2018, that's still only risen to 14 and a half so they're completely out of the market still, for me very early here.

Now COVID is obviously an accelerant on that but even today, we're probably further along than this graph now, it's still only about 27%-30% of the market that has been hit. There's still a long, long way to go.

It's interesting to sometimes think that the addressable market is much smaller than it really is and that we don't let these trends naturally play out as far as they can.

Here's a quote from the actual partner from Bessemer, Alex Ferreira, this is the person who believed the most, he was the one that pushed for it, that he couldn't comprehend that they'd have this amount of success in that much time.

A bit of an own goal really although an incredible return still.

Digital signage TAM

We've experienced a lot of this problem ourselves in our digital signage market, the industry analysts (there are not many numbers on this) have always predicted the addressable market would be around $19 billion of which would include a lot of hardware sales - software would be a mere $6 billion in 2018.

That's obviously quite small if you think back to what we were talking about with Uber and things like that, these are really very small numbers. But they don't really account for any disruption for different types of usage and I think there's a lot of industries where this is true.

But if we start to look more at the trends of software, I think they contradict this feeling quite a lot and this is also what we're seeing.

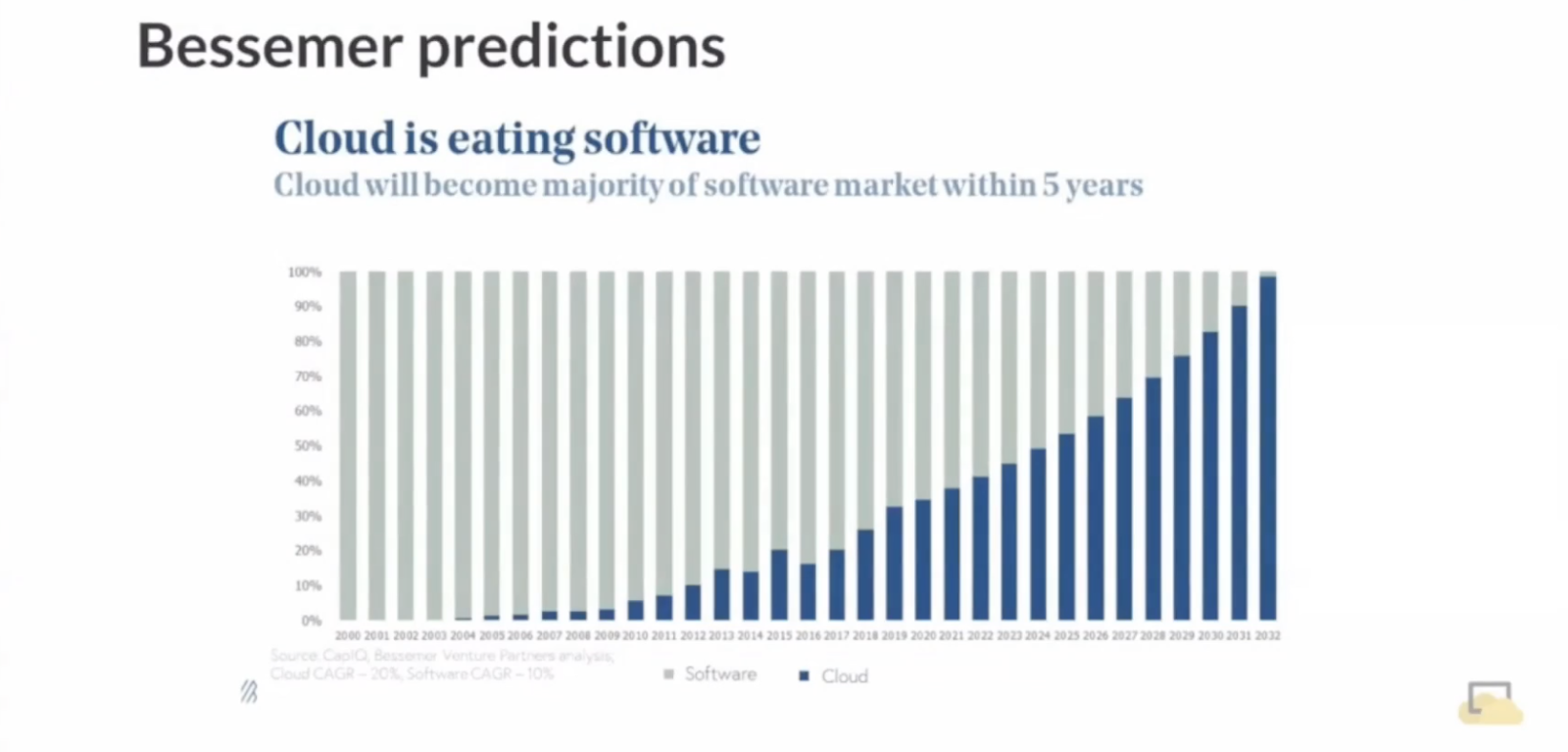

Bessemer predictions

If we look at cloud software, it's actually another Bessemer prediction here, Bessemer does the state of the cloud reports every year, and they talk about where cloud is going.

You can see here that cloud really is only just getting started. For me, cloud began in 2007-2008, when we first started using AWS services for some of our hosting. For me, it's been around forever but that's obviously very early days, thanks to my CTO and co-founder, Luke, who introduced me to it.

If you look today, and I think this graph here doesn't really account for any COVID kick at all, we're still only around 30% and I think it's going to kick on a lot more from that.

But the actual prediction, just by being in the cloud industry, is that by 2032, we're looking at basically 95% or 98%, of total market penetration of software delivered from the cloud.

Now, I suppose we're quite lucky calling our company ScreenCloud, we're very much based in the middle of this trend. Just by being here and surfing here, which is where our incumbents and older competitors don't exist, and probably many of yours don't either, they're not cloud-native and cloud-first, like many of your businesses will be, they're going to fall behind, and you're just going to be carried along by this rising tide.

Future trends

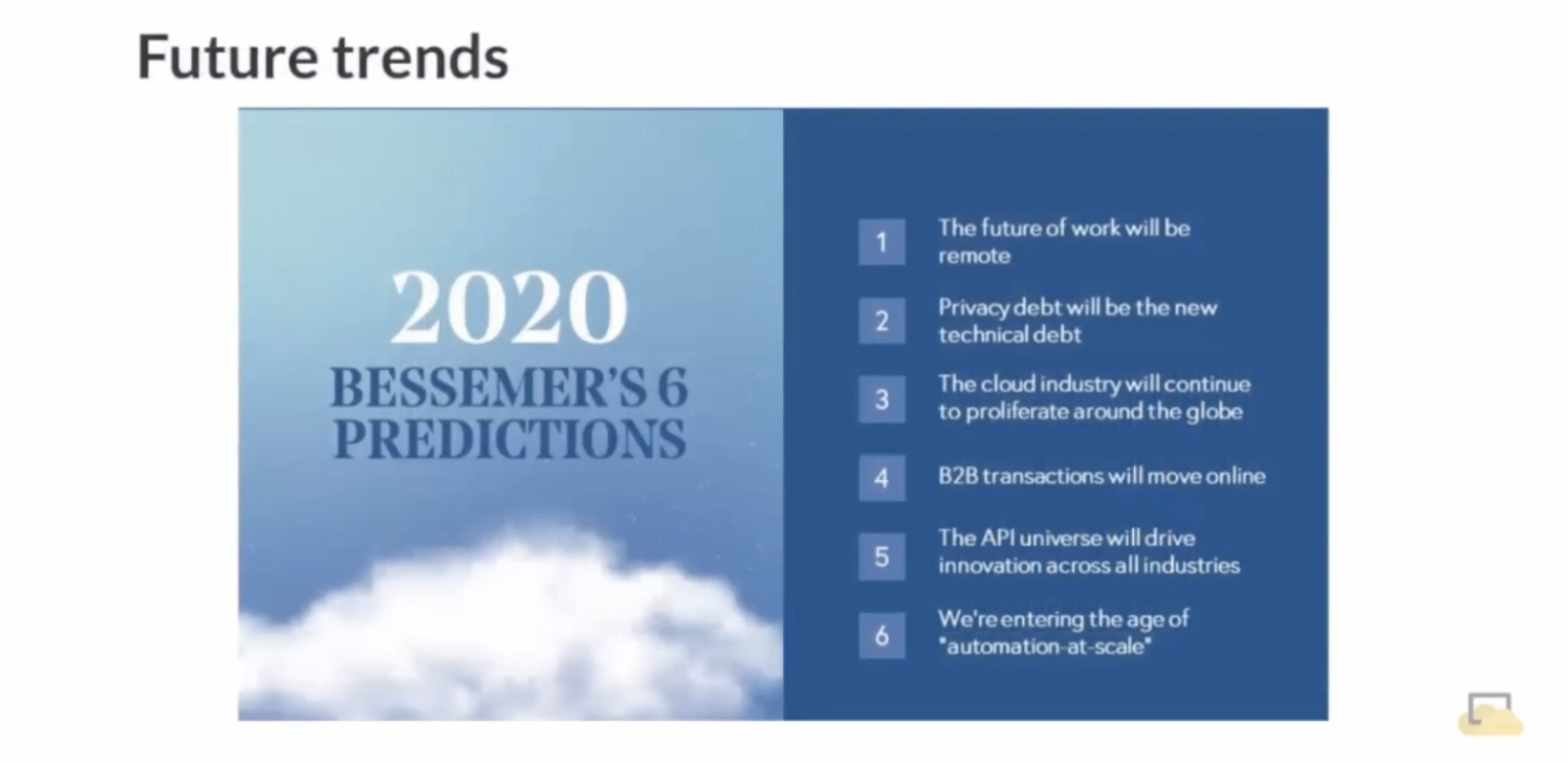

There are other predictions, which are fueling a lot of this as well. I think if we look at some of the other predictions Bessemer is mentioning, this is worth bearing in mind, for other waves or waves on top of this cloud that you can serve too.

The future of work will be remote

Firstly, that the future of work will be remote, or at least remote-friendly. I don't think the offices are going anywhere as such, but I think people will be working from home and from various locations as standard in the future.

This was a trend that was always coming but it's now coming at us quite fast and cloud really helps us achieve all of that. But we should be factoring it into our thinking even more.

Privacy debt will be the new technical debt

I think looking at privacy debt as a new technical debt is smart. We're in RFPs, we're increasingly seeing a lot of questions around where data lives, about privacy law in the EU, especially, and security constraints, and things like that are becoming increasingly important.

We can get ahead of ourselves by using the latest technology there and by architecting our solutions in a smarter way.

The cloud industry will continue to proliferate around the globe

Obviously, that the cloud industry is going to continue to proliferate around the globe and actually be reaching new countries and new markets all the time.

B2B transactions will move online

Transactions will move online more, this is an interesting one where actually, a lot of the customers we work with still pay for their invoices by cheque. So actually seeing more and more of these business transactions move online still seems mad to me and in the UK, we are actually pretty good at that.

But in the US there's still a lot being done through cheques and things like that. Again, there's more of a trend coming that way and that's going to open up to easier ways of selling online.

The API universe will drive innovation across all industries

I think being API first is absolutely crucial now, and it's going to drive innovation across a huge number of industries. I think that trend is also something we're feeling and seeing.

We’re entering the age of ‘automation-at-scale’

We're probably seeing a world where companies are going to have less large numbers of staff and using automation more. So think about how can you pull further automation to remove friction, to remove the need for human intervention, in a lot of your processes?

I think that's going to really fuel it.

Cloud is just getting going

To my mind, and I think to most people's mind, cloud is only just getting going. If we keep surfing this wave, there's a degree of inevitability towards what we can do.

The future looks very bright but I think we need to hold it longer and not do what often many founders do - jump off too early and think they've reached their peak when actually this thing is really only just going.

Conclusion

If we remove friction, we can increase our market size and surf the wave. If I look at ScreenCloud, we did a survey of our customers and 70% of our customers have never used digital signage software before.

So we are increasing our TAM by removing friction on sales, by lowering the barrier to entries in terms of hardware.

And I think by being open to the fact that we're using the latest cloud technology and web standards in our product, which is what customers are looking for increasingly, although right now still only a third of them are doing it so we have a huge way to go if we can just keep on pushing here and stay in the game.

I suppose that would be my other big message from this article.

If we do all of these three things well we make it rain...

Thank you very much.